It was late afternoon when we began preparations for a visit to Dehra Dun in the Himalayan foothills of Northern India. Before meeting him, Swami Jnananda Giri had suggested we take a dip in Mother Ganges to purify ourselves for the occasion. Now in his fourth stage of yoga, the great Swami had much to share with the students from our college.

His experience with yoga began when he was 23 and living in Switzerland. The day he received a copy of Autobiography of a Yogi was on March 7, 1952—the very day which Yogananda entered Mahasamadhi, a great yogi’s conscious death. On this day he set off on foot to India—never again to leave that holy ground.

Jnananda follows the traditional guidelines presented by his guru, Swami Atmananda, who was a disciple of Swami Kebalananda, Yogananda’s saintly Sanskrit tutor described in Autobiography of a Yogi.

Nakula and I were leading a pilgrimage to India with a group of college students. In India, the Ganges River is said to be spiritually cleansing.

Vedic traditions suggest yogis to take a dip in a sacred river before visiting holy people. I recalled a meeting many years ago when I first met Subramunya Swami in Hawaii when he was still alive. I was asked to walk through a shallow pool, cleansing my feet before entering their sacred temple. In the temple, women sat on the left, men on the right. It was a Hindu monastery that was striving to maintain the pure roots of Hinduism to the best of their abilities.

Taking a dip in the holy waters of the Ganges is straightforward for someone raised in India, where these customs are ingrained. I remember becoming squeamish when I first did this in 1987. Dunk my whole body into a freezing, fast moving river three times?

My mind was wondering whether or not I would be able to tie my sari on correctly for the ceremonial dip. On one of my earliest trips to India I was walking the crowded streets when I suddenly felt the entire contraption begin to slowly disengage. Once so gracefully draped around my shoulder and arm, the sari had become twisted into a blithering hulk that had snagged itself on my backpack. With every step I took it slowly unraveled. I made it back to our lodging facility with acres of cloth stuffed in the front of my pants, material hanging everywhere.

Yogis, Hindus, Buddhists and many Indians view the purifying Ganges River as a living Goddess. Spun from the heavenly realms of Brahmaloka, the mystical river is said to travel to earth from the abode of Lord Shiva deep in the Himalayas. Lord Shiva kept the Ganges safe in his hair, gradually letting her flow down through the Himalayas with his added blessings.

It’s considered sacred to take a bath in this holy river at least once in a lifetime. Hindus living near the Ganges can do this daily at dawn, along with chanting the sacred Gayatri mantra and performing other ceremonious rituals.

This trip to India, I decided to wear a white Punjabi outfit with pants and tunic for our ceremonial dip in the river. My husband Nakula, who surely must have been Indian in a recent incarnation, demonstrated the subtleties of ceremonial Indian bathing. Bravely strolling up to the Ganges in a dhoti, traditional Indian menswear, he waited patiently for the right moment to say a prayer, bowed his head, and submerged elegantly into the glacial water.

I sank down next to him and felt the water cover my face and head. Not knowing what to expect was helpful. A tingling feeling overcame me. The water had become droplets of radiant light that punctured my aura and sent me its silent blessing. My husband continued to dunk himself. I finished my dip and backed out of the river carefully.

We began our convoy to Dehra Dun in the old Ambassador taxis prevalent throughout India. Roads in India aren’t anything the linear Western mind can adequately understand. They are abstract, full of obstacles, animals, rickshaws and ancient vehicles. I watched as our driver pressed down on the accelerator and piloted around several large white Brahma Bulls, a motorized rickshaw and an oncoming bus we missed by inches despite the blaring horns.

The adrenalin of driving this way combined with the baptism by water had a fascinating effect.

We stopped midway for lunch at a South Indian café. Joining us for the occasion was Swami Bodhichitananda, the erstwhile “Surfer Swami” as he was affectionately known by our college students. All smiles and ushering us quickly into tables, Swami insisted we wash our hands first. He was American, seemed younger than most Swamis and wore the shaved head and orange robes of the Sivananda ashram, where he received his monastic vows from the late Swami Chidananda Saraswati. At one time he had been a sannyasi/monk with the Self Realization Fellowship in California, and now considered Swami Janananda his Kriya Yoga guru.

“Before we get to Dehra Dun we need to stop and get some food and Prasad for Swamiji,” he said. He explained that Jnananda is a traditional sannyasi who depends on others to care for him. I asked him what we should get. “Some good bread, jam, nuts and fruits,” he replied.

In India, Sanyasis who renounce the world usually wandered like mendicants, relying on donations from others. Traditional sannyasis also traveled by foot, though modern-day sannyasis travel by vehicles, even planes. A traditional sannyasi is homeless—it is one of the conditions. He or she must see the whole world as their home, not becoming bound by any one place. Giving up everything and living by God’s will and grace becomes the norm.

After lunch we all moved slower. Outside, our taxi convoy seemed half asleep as well and we searched for our driver. We boarded our ancient vehicle, my hands searching for seatbelts. I remembered they weren’t installed in these older models and had a flashback of American movies shown to 15-year olds on the virtues of seat belts. If I was to fly through the air like a plastic dummy, better it be while visiting a saint.

Our driver seemed to catch my thought and smiled at us in the rear-view mirror. A small statue of the Hindu goddess Durga sat on his dashboard, gracefully riding her tiger side-straddle, an array of weapons cascading from her eight arms, esoteric symbols of virtues like courage, detachment and righteousness. The driver swerved a few inches from a young man pedaling a bicycle. I closed my eyes, ducked and grabbed Nakula’s arm.

Approaching Dehra Dun, a simple sign with the words “sweet” stood above what appeared to be a storefront grocery. The taxi turned into a dusty space next to a few old motorcycles, narrowly missing an elderly man sitting on his haunches tending a cup of tea. Our driver turned off the engine, the old metal shaking and wheezing. He tossed a few words of Hindi to the man taking tea and they both smiled at each other and nodded their heads.

Inside, we hunted for Swami Jnananda gifts. Prasad, or sweets, are offered as a symbol of a seeker’s devotion and gratitude to the Divine. Once this offering has been blessed or sampled by a Divine channel, it is considered sacred and passed around to devotees.

“Oh, that looks good,” a student was pointing to fried donut holes floating in syrup.

The grocery store clerk packed up a large box of Gulab Jamun, wrapped it with paper, tied the box securely with colored string and handed it to Nakula with a big smile. “Very good,” the man said. Nakula looked at him and nodded. “Very,” the clerk paused and smiled again, “Sweet.”

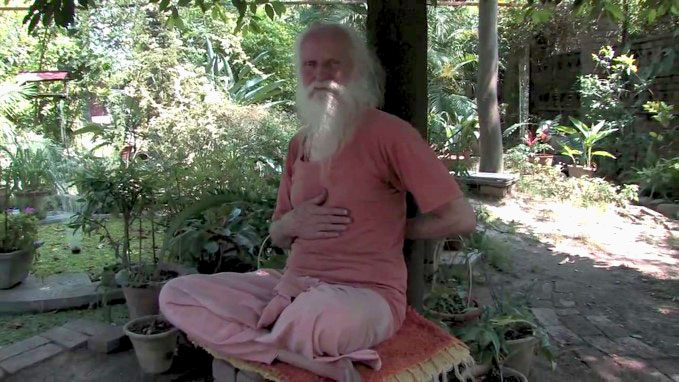

It was late afternoon by the time we reached Janananda’s home. It was actually the home of one of his devotees, and they had turned it into a small ashram. The swami greeted us with welcoming smiles and chatter. The first thing I noticed was that his energy appeared locked in his inner spine, no word or movement was wasted. His white beard was untrimmed and abundant, his long hair pulled up in a tiny topknot, rishi style.

The topknot, which is worn during the day, is meant to stimulate the frontal lobes of the brain, the area affected by meditation and deeper spiritual awareness. When the rishis wear their hair long in the evening the hair follicles are said to spread out and capture the energy of the ether and the moon.

The rishi’s hair has its own esoteric meaning. Many advanced yogis never cut their hair or beards, as the fine hairs are said to be transmitters and receivers of the subtle and psychic energy that we cannot see. The prana from the ether that sensitive rishis are able to capture is full of nutrients, able to sustain them without food.

There is a yogic belief that if you refrain from cutting your hair for three years it will grow to its natural desired length, giving the yogi increased subtle mental powers, patience and energy. To shave one’s head is also a ritual some yogis follow.

Just as a gardener prunes a tree to bring more energy to the pruned area, the same thing happens with the human body. Often yogis shave their heads on Shivaratri, one day before the new moon. The new moon is also an auspicious time to plant seeds in a garden. Like the tree that’s had its branches pruned, shaving the head is said to allow the energy of the body to move towards the two higher chakras in the head, especially the sixth chakra, which is located at the point between the eyebrows, and the seventh chakra, the lotus or crown chakra.

We were all watching Jnananda and listening. He ushered us into a large courtyard that was situated on a busy Dehra Dun street. During subsequent visits, his white hair was often pulled up Indian style in a turban. This was not a turban like many of the Sikhs wear, wound with accuracy and tightly tucked with precision.

On one visit Jnananda wore a casual turban, looking more like something I might have wrapped, coming apart in a few areas.

Though he was not a Sikh, many yogis, Hindus, Muslims and others throughout India wear turbans. Likewise, many Sikhs are also yogis. Since the time of their founder Guru Nanak they have worn the turban, called a dastaar, as a symbol of their Sikh faith.

The swami led us around the outside of his small ashram, beginning near the front and walking in a clockwise direction, circumambulating it three times, as is done with Hindu shrines. The building was round and two-story, covered with plant creepers that camouflaged it. It looked as though it was hiding in a jungle.

The courtyard garden was filled with trees and plants surrounded by soft dirt paths. Some of the larger trees had sitting benches tucked next to them.

“You should have your college students learn to walk barefoot on the earth,” Jnananda proclaimed. His accent was Swiss. “Doing so will allow them to connect to the earth’s magnetic field in a more profound way. They will learn subtle truths through this experience,” he said.

He took us to a tree in his garden and sat lotus style on a bench, pulling his back right up next to the tree. “This tree has healed me of sickness many times,” he said. He demonstrated how to do this, putting one’s left hand behind the body and against the tree, as to draw energy from the tree. Then, the right hand is placed across the heart chakra, so as to channel healing energy from the tree into your body.

“You should try this,” he said. “Trees can be powerful healing instruments with much more knowledge than we are aware of,” he continued. He suggested that we use only the healthiest of trees. “A healthy tree lovingly cared for can become our ally,” he said.

He had spent his entire adult life living close to nature.

Rishis of Vedic India lived in remote forests in harmony with wild animals. In no other part of the ancient world is there such nonviolence and compassion for animals. Even the great Buddha’s compassion stemmed from the spiritual ethos of India.

“In higher ages the rishis use trees to communicate across long distances,” he said as we listened. Trees are noble beings, especially those that have been on earth for hundreds, thousands of years.

This is an excerpt from a chapter of Nischala Cryer’s book, The Four Stages of Yoga. Trips to India with Ananda College are always different, each seemingly created by the unique karma of the group.

This is an excerpt from a chapter of Nischala Cryer’s book, The Four Stages of Yoga. Trips to India with Ananda College are always different, each seemingly created by the unique karma of the group.

To read more stories of travels with Ananda College, you can order The Four Stages of Yoga by Nischala Cryer from Amazon. The book also chronicles the Ananda College private audience in 2005 with His Holiness the Dalai Lama of Tibet at his home in Mcleod Ganj, India. Nischala also shares stories of her meetings with Mother Teresa of Calcutta in 1978. The book became a bestseller in June of 2018.